Sound-absorbing reversible curtain fabric by Margarete Leischner, 1927 (Bauhaus Foundation)

The object is a ‘sound-absorbing reversible curtain fabric’ designed and manufactured by Margaret Leischner in 1927. It is located within the ‘Factory as Horizon’ display that runs across the spine of the ‘Versuchsstätte Bauhaus’ exhibition at the Bauhaus Museum Dessau (Bauhaus-dessau.de, 2019). Despite being produced over 90 years ago, the fabric appears to be in good condition. It has a multicoloured striped pattern and according to the museum catalogue ‘Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, The Collections’, is made from wool, cotton, chenille yarn and linen weave (Bernhard et al., 2019, p.188).

Being exhibited under a glass box, the fabric expresses itself in several shades of blue and amber, alternating with each other. Upon close inspection, the intersections between blue and amber strands form several rectangle blocks. The pattern of the fabric can be divided into four parts according to the different shades of colours that each block presents. They are light blue, dark blue, light amber and dark amber. Placing next to each other, they create a diversity within the unity of the pattern as well as a gradient effect that is observable from afar. The fabric is 307 cm long and 163 cm wide (Bernhard et al., 2019, p.188). However, only a part of it is visibly displayed at the Bauhaus Museum Dessau using a wall-mounted roll-up system. Compared to its neighbor exhibits, the fabric is ostensibly thicker, allowing it to appropriately serve as a sound-absorbing material and become functional.

The fabric was created by Margaret Leischner, titled Royal Designer for Industry (RDI), a German-British textile designer and a former student at the Bauhaus (Otto and Rössler, 2019, p.109). Leischner attended the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop in Dessau from winter semester 1927 to winter semester 1930-1931 (Bernhard et al., 2019), therefore ostensibly produced the fabric during her first few months at the school. During her exile in England, Leischner contributed to advancing the Bauhaus theory and was one of the few who succeeded in pursuing textile design as a career (Weltge-Wortmann, 1993, p.12).

Leischner arrived in Dessau shortly after the Bauhaus’s struggle for a status that was more ‘than an arts and crafts school’ and ‘another school for the applied arts’ (Weltge- Wortmann, 1993, p.53). Meanwhile, at the same time, the students at the Weaving Workshop were confronted with different kinds of hardship: the gender issue and a lack of attention as well as financial support. When it first opened the door to students, the Bauhaus promised an ‘equality in the choice of a profession’ and use of spaces for ‘…any person of good repute, without regard to age or sex, whose previous education is deemed adequate by the Council of Masters’ (Weltge-Wortmann, 1993, p.41). However, it quickly revealed that female students were only allowed in, or rather, ‘directed’ into the three workshops of Weaving, Pottery and Bookbinding with the latter two eventually removed from the curriculum due to a lack of interest (ibid). As well as in the social norm, the hierarchy of art and design placed textiles and women at an equally low position (Weltge- Wortmann, 1993, p.9).

‘…Their role within the institution was defined and formulated by their teachers. Only then did it become apparent that they were assigned talents and capacities viewed as innately female, of which a special predilection for textiles was only one.’ (Weltge-Wortmann, 1993, p.52)

After Walter Gropius’s early withdrawal from his position as the director of Bauhaus in October 1927, the school expeditiously shifted its focus from a unity of art and technology to a ‘socially oriented pragmatism’ under the new direction of Hannes Meyer (Weltge- Wortmann, 1993, p.108). Meyer’s vision for the Bauhaus was manifested through ‘functionalism’ and his goal to ‘orient all design activity toward mass production’ (Weltge- Wortmann, 1993, p.109). He addressed it clearly during a meeting with the students:

‘…Do we want to be guided by the world around us, do we want to help in the shaping of new forms of life, or do we want to be an island?’ – (Meyer, 1928, as cited in Weltge-Wortmann, 1993, p.109).

Meyer’s agenda put emphasis on mechanical equipment as an instrument to experiment new techniques and designs for industrial production. This led to a recurring debate centered around the use of hand-weaving versus industrial machine-weaving at the Bauhaus, especially among the students of the Weaving Workshop (Weltge-Wortmann, 1993, p.97). Apparently, an increase in the employment of technology didn’t mean the students would gain access to a more diverse resource of materials. Most students, including Annie Albers, had difficulties in working with what was considered as a ‘not very subtle’ option of colours, or ‘without a personal choice’ (Weltge-Wortmann,, p.94).

In line with the Bauhaus’s ideology at that time, Leischner’s piece of fabric was considered to be cost-effective and modern due to its rib weave construction and striped pattern (Bernhard et al., 2019, p.188). Rib weave is a variation of plain weave, where the warps – threads that run longitudinally and the wefts – threads that cross it, are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric and facilitates changes in colour (Eryuruk and Kalaoğlu, 2015). It is commonly used to strengthen plain fabrics or develop woven fabrics for heavy application area as they only stretch on the bias directions (ibid). Through the use of different shades of blue and amber, Leischner inevitably transformed the appearance of the plain structure, making it seem simple, yet sophisticated. This, perhaps, is a ‘mutual benefit’ of the combination between hand weaving and technically ‘superior’ mechanical weaving that Otti Berger – one of the most talented students at the weaving workshop – once had faith in (Weltge-Wortmann, 1993, p.113-114; Weibel, 2005, p76).

A Jacquard loom was presumably employed to fabricate Leischner ’s design. Invented by Joseph Marie Jacquard in 1801, the Jacquard loom employs punched cards as a formula for automatic selection and pulling of cords which lift the warp in a pre-planned pattern (Science and Industry Museum, 2019). During the Bauhaus days, the cards were punched manually by hand. It was a time-consuming task that required precision and permitted no errors (Weltge-Wortmann, 1993, p.104). However, for Anni Albers – head of the weaving workshop from 1928 – the Jacquard loom was an ideal tool because of its ability to render ‘her geometric designs into crisp, flat textiles with precisely articulated lines’ (ibid).

Like many other textiles produced at the Weaving Workshop in the 1920s, Leischner ’s woven fabric was designed to fulfil an ‘intended aesthetical and functional purpose’ (Weltge-Wortmann, 1993, p.187). Being reversible and sound-absorbing, it was originally intended for the production of curtains (Bernhard et al., 2019, p.188). The Bauhaus Foundation acquired the fabric from a private collection in 2006 before displaying it as a part of the exhibition at the Bauhaus Museum Dessau in 2019. Little information has been revealed on the fabric’s journey outside of the Dessau Weaving Workshop. One could only speculate that since the Bauhaus officially owned all of its student works (Weltge- Wortmann, 1993, p.95), Leischner original creation was probably marked with the signature Bauhaus aluminium tag before it headed out to the ‘broad market’ as a commercial, functional piece of textile.

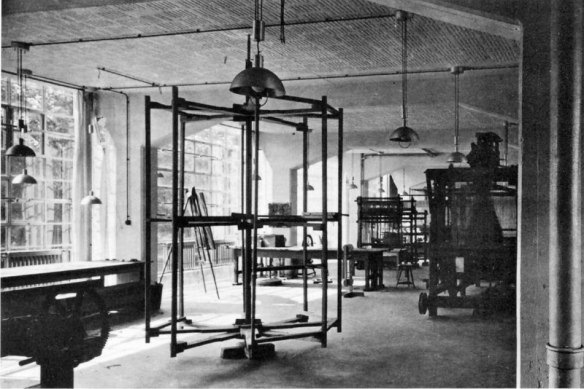

The weaving workshop, 1927 (Bauhaus Foundation)

It is important to mention the prevalent use of the Bauhaus Weaving Workshop products in architecture and everyday life. Although ‘function’ and ‘production’ were perceived as a threat to the artists’ ‘inner needs’ (Weltge-Wortmann, 1993, p.53), they also proposed a great challenge to the weavers: ‘If fabrics were to become an ‘integral’, even ‘subordinate’ part of the modern building, the role of the designer had to change as well’ (Weltge- Wortmann, 1993, p.101). According to Gunta Stölzl – the Bauhaus only female master – weavers should begin their design process with the end use of the material in mind (Müller, 2009). Elements such as structure and technical specifications must be considered and dealt with in a systematic manner (Weltge- Wortmann, 1993, p.102). An example being Anni Albers’s famous curtain and wall- covering materials that she designed for the Educational Centre of the Trade Union auditorium in 1930 (Weltge-Wortmann, 1993, p.104). By using a combination of black and silvery threads, interwoven with a cellophane front and a chenille, Anni single- handedly came up with a new, scientifically-proven way to effectively increase light reflection and sound absorption (ibid). Her structured approach to design, research and problem solving was undoubtedly advanced at the time. It resonated deeply with other Bauhaus designs and pedagogical disciplines and ultimately enabled the weavers to develop a ‘language of design’ – one that become timeless (Weltge-Wortmann, 1993, p.188).

A question concerning the impacts that Josef Albers’s preliminary course might have had on Margaret Leischner’s learning and personal aesthetic development process could offer the audience a better understanding of her decisions regarding colour, material and technique. Subsequently, a comprehensive exploration of Josef Albers’ creative works and philosophy during the time of Leischner ’s admission could also reveal further information on the production of the object, as well as their relationship as student-teacher and later, as colleagues at the Bauhaus.

Bibliography:

Bauhaus-dessau.de. (2019). The architecture of the Bauhaus Museum Dessau by addenda architects from Barcelona. [online] Available at: https://www.bauhaus- dessau.de/en/museum/architecture.html [Accessed 20 Oct. 2019].

Bernhard, P., Blume, T., Markgraf, M., Schöbe, L. and Spehar, J. (2019). Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, The Collections. Bielefeld: Kerber Verlag.

Eryuruk, S. and Kalaoğlu, F. (2015). The Effect of Weave Construction on Tear Strength of Woven Fabrics. Autex Research Journal, 15(3), p.207-214.

Müller, U. (2009). Bauhaus Women. Paris: Flammarion. p. 42.

Otto, E. and Rössler, P. (2019). Bauhaus Women. London: Herbert Press.

Science and Industry Museum. (2019). Programming patterns: the story of the Jacquard loom | Science and Industry Museum. [online] Available at: https://www.scienceandindustrymuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/jacquard-loom [Accessed 21 Oct. 2019].

Weibel, P. (2005). Beyond Art: A Third Culture: A Comparative Study in Cultures, Art and Science in 20th Century Austria and Hungary. New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

Weltge-Wortmann, S. (1993). Bauhaus Textiles: Women Artists and the Weaving Workshop. 1st ed. London: Thames Hudson.