In his early days as the new director of the Bauhaus, Hannes Mayer asked his students: “Do we want to be guided by the world around us, do we want to help in the shaping of new forms of life, or do we want to be an island?” (Meyer, 1928, as cited in Weltge-Wortmann, 1993). Meyer’s directorship led Bauhaus through the most productive period it ever witnessed in 14 years of operation, albeit going against other renowned teachers’ ideology at the time such as Wassily Kandinsky and Walter Peterhans, who perceived function and production as a ‘threat’ to arts and their ‘inner need’ (ibid.). With his questions, Meyer advocated for an alternative approach to design, one that was more pragmatic and socially oriented.

Much in the same way, Victor Papanek called for designers to be world citizens and advocated meaningful collaboration that responded to the needs and desires of ordinary people. The myriad of question marks used in Papanek’s iconic literature ‘Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change’ (1971) reifies his passionate cri de Coeur towards the practice of irresponsible design. According to Papanek, in his original words, ‘design can and must become a way in which young people can participate in changing society’ (Papanek, 1971). He considered ecological and social responsibility as the twin pillars of design practice. Starting with the enticing ‘What is Design?’, Papanek begun to raise his concerns regarding several issues in the field of product design, architecture and city planning, which he considered as wasteful, useless, bad for the environment and neglected from the humane factors. He then continued with a more condemnatory tone in ‘Where has our spirit of innovation gone?’ and straightforward ‘Are we still designing for minorities?’ (ibid.). These questions, taken out of context, still echo with the challenges we often face in today world – the world which we founded on a naive assumption that our resources are indeed infinite and inexhaustible.

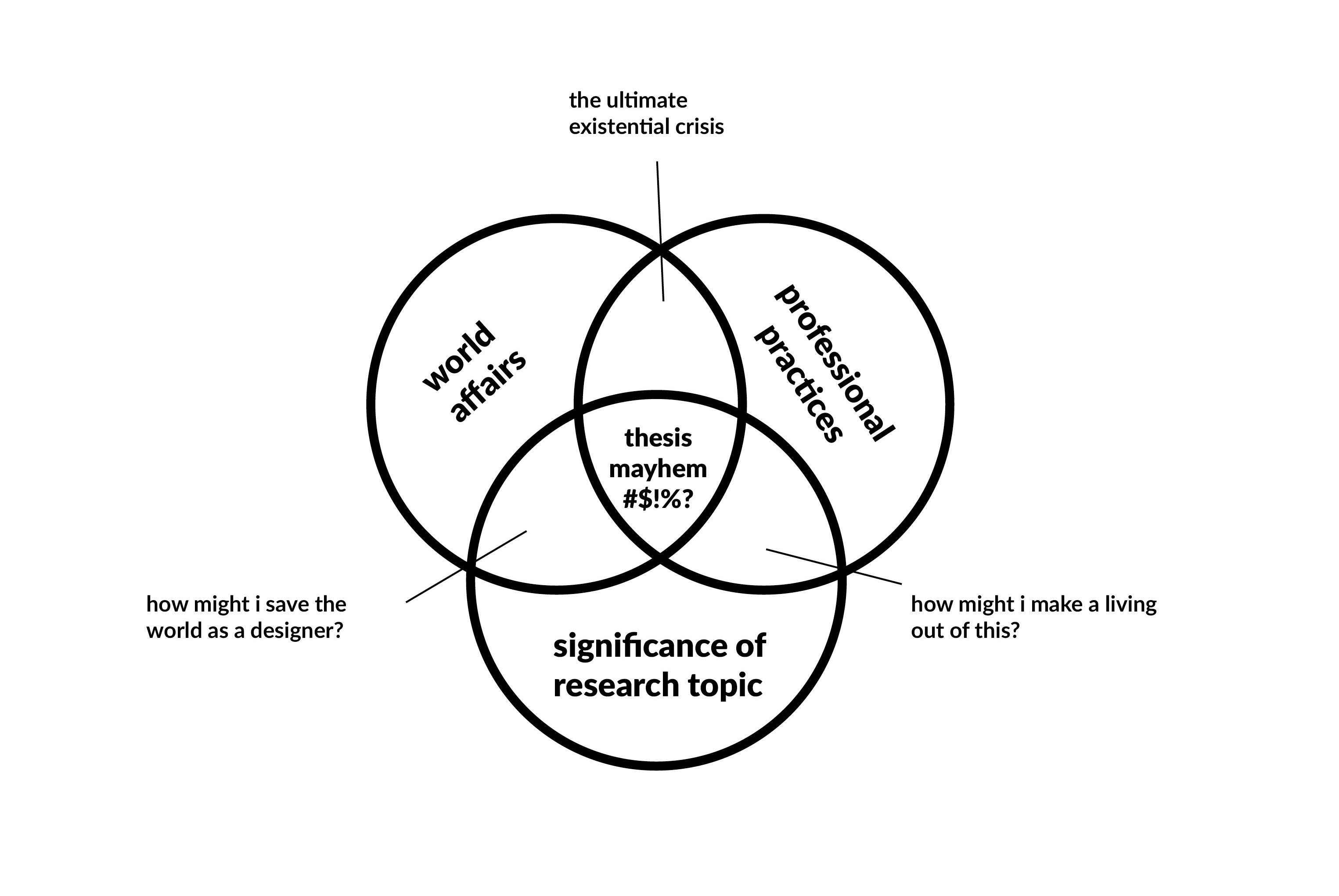

Papanek originally published his work in 1971 and revised it in 1985. Hence, some of the examples in the book might become impertinent to our digital age. However, his vision for integrated design and cross-functional team as a problem-solving method has reached far beyond the boundary of literature. As Papanek’s advocacy for a better way of design, his philosophy formed the basis for many contemporary design approaches and principles such as those of Social Design, Humanitarian Design and Human-centered Design. An up-to-date equivalent to Papanek’s text, I reckon, would be ‘Change by Design’ written by Tim Brown in 2009. In his book, Brown introduced the concept of Design Thinking as a versatile approach to creative problem-solving. By asking ‘How might we?’ instead of the conventional questioning method and applying the iterative design process in their practice, design thinkers are set to discover not only meaningful insights of the social, cultural and historical aspect of the challenge, but also a deeper understanding of the people whom they design for (Brown, 2009). In this sense, asking questions is of the essence to the Design Research process. Asking the right ones then, becomes a critical part of the designers’ job, for there the ability to cultivate stronger arguments, clarify goals, observe the inconspicuous and ultimately make design better.

we seek to achieve the wildest possible survey of the people’s life,

the deepest possible insight into the people’s soul,

the broadest possible knowledge of this community.

as creative designer,

we are the servants of this community.

our work is service to the people.

– Hannes Meyer, as cited in Claude Schnaidt, 1965.

Being present at the Bauhaus building in Dessau as a design research student and a creative practitioner working in the humanitarian sphere, I’m learning to foster my professional approach around the question of ‘How might we employ design as a catalyst for positive changes?’. Framing today’s wicked problems is already a daunting task. Solving them, requires more than just a refined solution. Design Research, thus, when embracing an ethical axis like such mindset of Meyer and Papanek, initiating multidisciplinary effort and exercising iterative hypotheses, then, and only then, should it be able to bring about social impact. My question, whether appropriately proposed or not, will remain unresolved in the meantime, for I still have more to learn, to explore and to observe.

___

Brown, T. (2009). Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation. USA: HarperCollins.

Schnaidt, C. (1965). Hannes Meyer: Buildings, Projects and Writings. Teufen: Niggli AG.

Papanek, V. (1985). Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. 2nd ed. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

Weltge-Wortmann, S. (1993). Bauhaus Textiles: Women Artists and the Weaving Workshop. 1st ed. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.